For many Floridians, there’s only one way to spend the Fourth of July – at the beach. Each year, thousands commemorate our nation’s freedom by flocking to the roughly 600 beaches of coastal Florida. As fireworks paint the sky shades of red, white, and blue, friends and strangers sit shoulder to shoulder on the shores below – a fitting celebration of the hard-earned rights, majestic natural lands, and solidarity shared by fellow Americans. And Floridians have long taken public beach access as a right.

Cape Coral: the largest 4th of July fireworks display in Southern Florida.

On Independence Day this year, however, those in the Sunshine State will have a bit less liberty to celebrate – and a lot less beach on which to do so.

A newly passed state law allows Florida’s waterfront property owners to restrict public access to the sandy shores that fall within their property lines. Signed a few weeks ago by Governor Rick Scott – despite the impassioned opposition of thousands of activists and beachgoers from throughout the state – House Bill 631 effectively strips the people of Florida of their right, which has been protected since the state’s inception, to recreational access to the state’s coastal lands.

Public Access to Florida Beaches: A Brief History

The relationship between public beach access and private property rights is a sticky, often complicated issue that has been the subject of countless legal disputes between private owners and municipal or state governments.

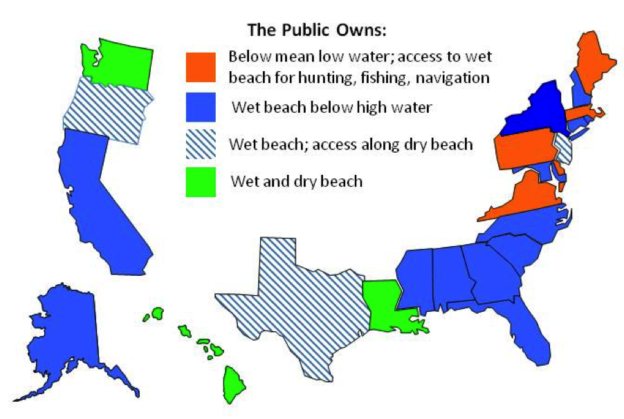

Public trust doctrine – the ancient legal principle that governments may protect certain natural resources for public use – has long maintained the common law right of state governments to hold in trust all beaches for public use. Today, each individual state is responsible for articulating, interpreting, and enforcing the particular guidelines that determine which beach land may be designated as public.

In Florida, coastal land below the “mean high water line” – all parts of the shore that become awash during high tide – have been arduously defended by municipal governments as open to the public, irrespective of private property lines. Wet sand has always been treated as belonging to the public domain, and while many beachfront property owners have fought to restrict public encroachment on their land, public trust doctrine has routinely been used to maintain the right to public access.

Local governments have often adopted “customary use ordinances” to preserve these rights, by identifying the state’s long and storied tradition of public use. In a landmark ruling in 1974 – City of Daytona Beach v. Tona-Rama, Inc. – the court enforced the public’s right to access a privately owned stretch of Daytona Beach by citing the deep, long-established connection between Florida’s coastal lands and its inhabitants: “No part of Florida is more exclusively hers, nor more properly utilized by her people,” the ruling proclaimed, “than her beaches. And the right of the public of access to, and enjoyment of, Florida’s oceans and beaches has long been recognized by this Court.”

The case also established a legal precedent that would yield enormous influence in similar disputes in the decades that followed. “If the recreational use of the sandy area adjacent to mean high tide has been ancient, reasonable, without interruption and free from dispute,” the court reasoned, “such use, as a matter of custom, should not be interfered with by the owner.” The case of Trepanier v. County of Volusia, in 2007, helped establish a means by which customary use could be systematically proven, through “eyewitness testimony, expert testimony, and aerial photographs of the general are of the beach.” Often, just a longtime local’s testimony, together with old family photographs of a trip to the shore, would be enough to establish customary use, and public beach access, within a contested beach region.

But those days are over. With the passage of HB 631, it is no longer in the hands of municipal governments to proclaim customary use; now, that capacity belongs solely to judges. Under the new law, customary use can only be proven in court, on a case-by-case basis, using ample and convincing evidence. Local governments no longer have the legal right to enforce public beach access to private beaches by passing customary use ordinances; the process has been moved to the judicial realm.

While private property owners previously had to build their case, the onus is now on members of the public to obtain judicial affirmation of customary use. To put it another way: for years, Florida’s coast was regarded as public until proven private, but now, it is private until proven public. Beachfront owners are now legally allowed to prohibit the public from walking along the sands above the high-tide line, whether by roping off parts of their beach property, constructing fences, or putting up signs.

Opponents of the new law assert that it benefits a few at the expense of many. Public beaches, they argue, are the heart of Floridian culture, extending all the way back beyond the state’s beginnings. Others warn that the ruling will cripple Florida’s tourism industry – the lifeblood of the state economy.

It is no coincidence that we celebrate our nation’s freedom and solidarity all along our coastal lands. In commemorating our nation’s independence, we celebrate the rights afforded to us as a result of our freedom – the hard-fought liberties it is our obligation to preserve. Chief among them is our right to enjoy the beautiful shores of our nation’s coasts.

As thousands of Americans descend upon the shores of the Sunshine State this Fourth of July – just three days after HB 631 officially goes into effect – we may do well to remember what it is we are celebrating. We may do well to remember the words to an old folk tune we know so well – a Woody Guthrie song that has been hailed, appropriately, as a national anthem in its own right – and which has become, to many Americans, synonymous with Independence Day celebrations:

“This land is your land, this land is my land

From California, to the New York island

From the Redwood Forest, to the Gulf Stream waters

This land was made for you and me”

And we may do well to remember an earlier version of the song, with a lesser known but particularly timely verse:

“There was a big high wall there that tried to stop me.

The sign was painted, said ‘Private Property.’

But on the backside, it didn’t say nothing.

This land was made for you and me.”